On April 4, 1968 at 6:01pm (or 6:05 p.m. depending on your source), Martin Luther King was assassinated by a white man named James Earl Ray.

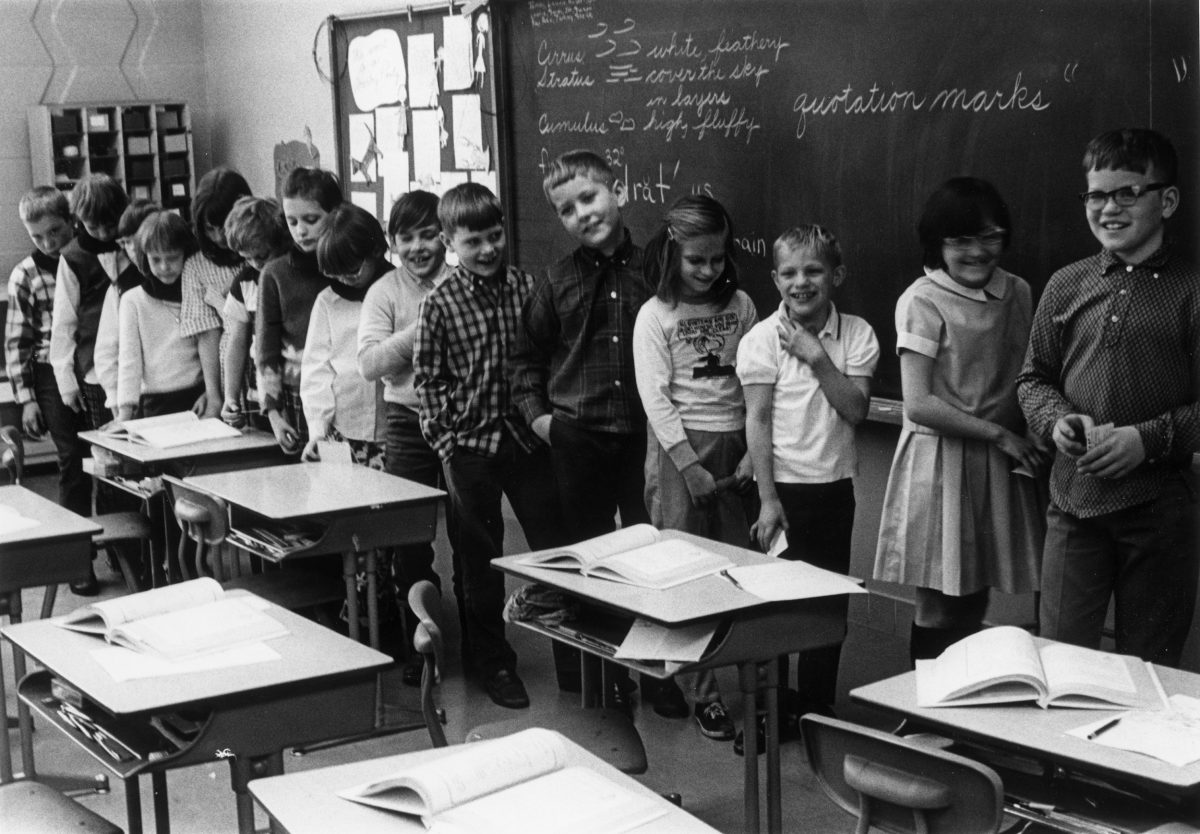

The next day, Jane Elliot, a third grade teacher in Riceville, Iowa, decided to teach her kids about racism. For the next week, third graders with brown eyes were given privileges, extra time at recess, front seats during class, that sort of thing. Kids with blue eyes sat in the back of the rooms, had shorter recess and less respect.

“I watched wonderful, thoughtful children turn into nasty, vicious, discriminating little third graders,” she says of the experiment.

The following week the kids switched roles: the blue-eyed third graders became privileged; the brown-eyed kids became under-privileged.

Each week, those with privilege were happier, more confident, and did better in school. Those without privileges became depressed, lost confidence, and performed poorly in school.

Jane Elliot continues teaching her “Blue-eyes/Brown-eyes Exercise”, in various ways and to all ages, to this day.

You’d think that would have changed the country, right?

Look around.

Three years later, in 1971, Stanford psychologist Philip G. Zimbardo got a grant from the US Office of Naval Research, to conduct the Stanford Prison Experiment. He had a mock jail constructed in the basement of one of the school buildings and divided 24 Stanford students into two groups: prisoners and guards. Each student was paid $15/day. The prisoners were placed into eight cells, with three people in each. The experiment was designed to last two weeks, just like Elliot’s.

Zimbardo encouraged the “guards” to establish an atmosphere of oppression and tyranny, duplicating prisons across the country. As with Jane Elliot’s third graders, the Stanford “prisoners” immediately became depressed; some became rebellious. The experiment was so traumatic that five “prisoners” were released within four days, the entire experiment cancelled after six days.

”Only a few people were able to resist the situational temptations to yield to power and dominance while maintaining some semblance of morality and decency;” said Zimbardo later in his book The Lucifer Effect”.

You would think that, so soon after King’s murder, the clear proof of what unbridled power and racism – for those who have it and those who are subjected to it – does to humans in those two events, would have swept the nation and brought about immediate change, right?

Look around again.

Both stories have appeared in books, on TV shows, and a movie, for years. Did they change anything? Nope.

So that’s pretty scary.

But the key to these two stories, to me, is not the cruelty; it is the speed with which cruelty was implanted in these students. It didn’t take months or years or generations, as we all tend to assume when we talk about racism. It took a day, maybe. And reached down into the very soul of those involved.

Humans have always been pack animals. It’s an instinct that saved us from the predators, not to mention pandemics… and wars.

When students start in a new school, they immediately become loyal to the new school and student body. When we move from one city to another, we become loyal to the new city’s sports teams. We become loyal to our company, our clubs, our new friends’s friends. Leaders, whether education, military, corporate, or political, count on that loyalty to fuel success.

It’s why many of us have so easily been turned into racists.

That’s the bad news. And the good news.

Richard Yacco, one of the student prisoners, who teaches at an inner-city school in Oakland, California said, “One thing that I thought was interesting about the experiment was whether, if you believe society has assigned you a role, do you then assume the characteristics of that role?”

His answer: people “fall into the role their society has made for them.”

If society’s leaders – be they schoolteachers, college professors, corporate CEO’s, or US Presidents – can assign us the role of racists, they can just as easily assign us the role of non-racists.

Good leaders can influence societies, can assign us new roles. It may have taken 400 years for white Americans to see our racism. But it doesn’t have to take that long to turn it around. Philip G. Zimbardo and Jane Elliot have already proven that.

To do that we need good leaders, more and more of them, until we all take on the same role and race: human.