My kids, all of whom are brighter than the average lightbulb, were no exception to the “Kids are curious” rule. As a good father I learned early on to answer all their questions truthfully and thoroughly.

Take Santa Claus, for example.

One day one of my kids found out from a friend that his mother had been a little more wistful than truthful in explaining the bearded giver. And I had been way too busy re-reading the back of the cereal box to contribute.

The power of giving? I can explain that any day of the week. The notion of being thankful? In a second. But Santa? Uh….

The news from his friend devastated him. And us. Until the dog started barking in empathy and then chased the cat straight into the Christmas tree, which shed ornaments like snowflakes (except with more noise), which led to a few well-expressed sentiments from his mother, which made my son laugh.

Which happily ended the discussion about Santa.

His mother and I were so devastated by his sadness that no more children were produced for what felt like years. And then we had two at once, which, I explained to him, was a result of waiting so long.

Having lots of kids has taught me the art of explaining things I knew nothing about.

Electricity, for example. “Dad?” he asked one day at around four years old, as I tucked him into bed, “how does a lamp know when to turn on and when to turn off?”

“Easy”, I said. “The magic in your back.” I walked over to the wall switch and leaned against it. “Let me show you.” I rub my back up and down against the switch and Presto! – the lamp turned off and then on.

“Oh.” He nodded thoughtfully. Then, “Dad? The switch is too high for a little kid. How do I turn it on and off?”

“You call me or your Mom.” I gave him a kiss good-night and turned off the light with my magic back on the way out.

Or take toilets. By four, he knew how to use one, but hadn’t really considered how they worked until one day when I was changing his new sister’s and brother’ diapers.

“Ew!” he said. “That smells, Dad!”

“Yes, it does”. I said. “It’s worse than smelly fish. That’s why we teach kids about the toilet as early as possible.”

“Boy, I’m glad you taught me about toilets!” Then, “ but how do they work, Dad? And where does it all go?”

My first thought was to run and get his mother, but I controlled my fear. “Well”, I said, “that’s hard to explain”.

“And what about the pee-pee. Does it go to a different place than the poo-poo?”

“Uh… no. It all goes to the same place”. I took him into the bathroom. I raised the lid of the toilet. “See down there?” I said, pointing to the water.

“That’s where it goes” – closing the lid – “and then, we turn this handle” – turning the handle – “And…” a great whishing sound filled the room.

“…That’s the ThroneMan taking it all away!”

“What’s a ThroneMan, Dad?”

“He’s the invisible King of the bathroom. He keeps the toilet clean.”

“But…where does he put all the —?”

“—That’s one of the mysteries of life, Korwin.” I say sagely. “Like where flies go in the winter or why ice cream tastes so good.”

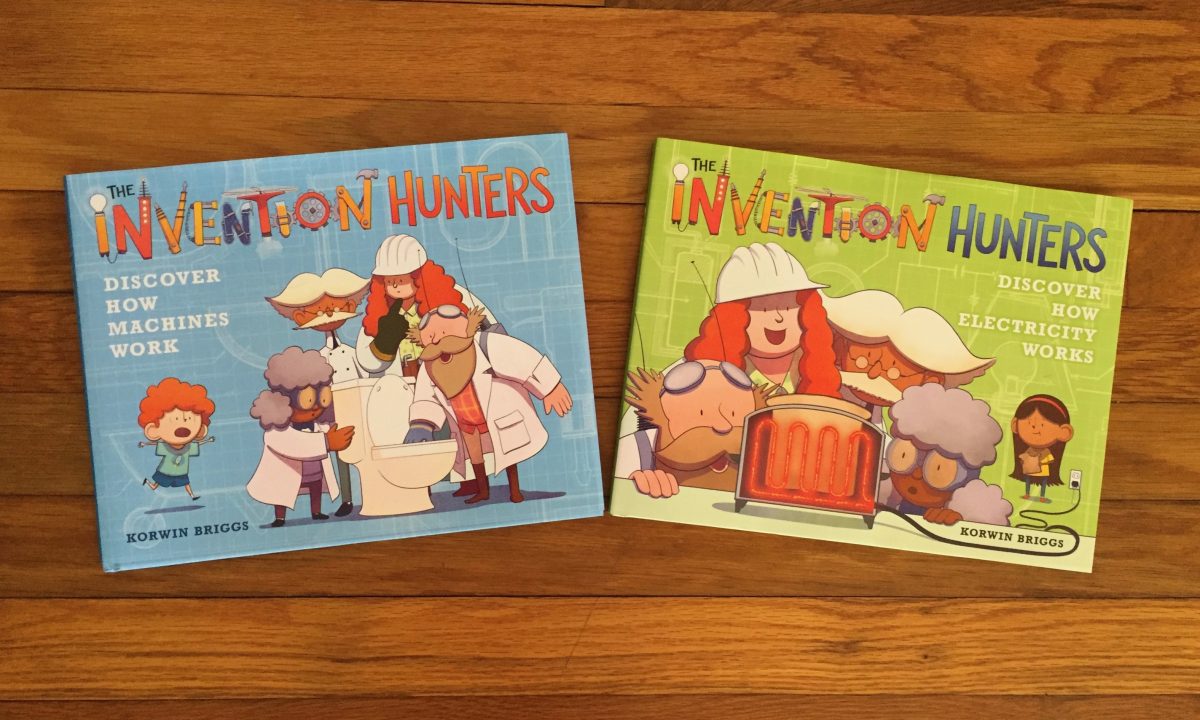

I thought that ended the discussion until early last week, when I was in the Children’s Section of a book store and discovered two in a series of new children’s books called The Invention Hunters. One explains electricity, the other machines, including toilets. Both are aimed at kids 4 and up.

It was very upsetting.

You see, the kids in the books are the smart ones. The grownups, The Invention Hunters, are doofuses. They tumble down from a rocket-ship house in search of new inventions for their Museum of Inventionology. Everyday objects trigger intense curiosity – and childlike guesses – from them. A little girl and boy (looking suspiciously like a 4 year old I once knew) patiently explain how these things work.

My favorite part is the picture of a fish going down the toilet.

(The Invention Hunters was written and illustrated by a constantly curious ex-four year old, Korwin Briggs, and published by Little Brown and Company.)